Whatever the approach taken, the need to innovate in the construction industry is one recognized by building professionals, investors, ordinary citizens, housing activists, economists, the list goes on. To understand some of the reasons why the construction of homes and other buildings in North America has struggled to see the gains of other industries, we need to understand where we are now, where we’ve come from, and where we’re going. We start with a word on the third industrial revolution…

The Third Industrial Revolution

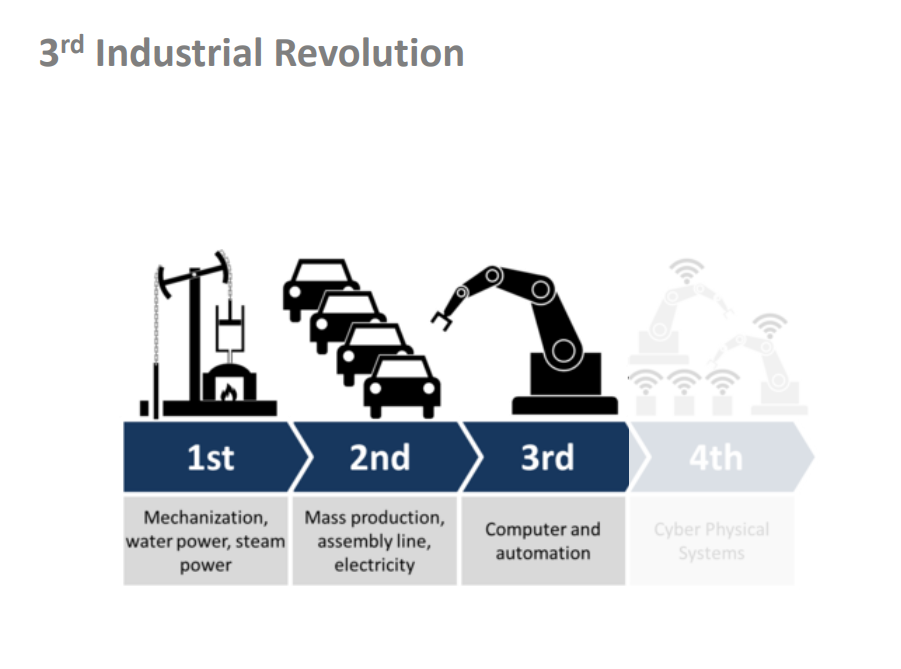

Dr. Guido Wimmers, a pioneer of Passive House construction in North America and the Program Chair for the Integrated Wood Design Program at the University of Northern British Columbia, likes to express the need for prefabrication in construction by providing the somewhat puzzling contradiction of how far behind the construction industry is when it comes to following the progress of the first, second, third, and even fourth industrial revolutions. He represents the first with the invention of mechanization, water systems, and the steam engine, the second with the Model T Ford and Henry Ford’s assembly line, the third with the computer age and information technology, and the fourth with the incorporation of connected, intelligent systems and artificial intelligence. Where does construction lie, he often asks his audience? Another simple question – would you buy a car if they delivered it to your doorstep in pieces and you had to hire a company to put it together for you?

The 20th century – kit homes, mobile homes, and modular buildings

When we think about Guido’s question, we’d find it hard to argue that we’ve really accomplished anything in construction beyond the first industrial revolution. We use power tools, sure, but have we even started using the assembly line? Well, the fact is, we did go that route in the past once before, but it’s a history that we’re not so sure took as to all the right places – yet.

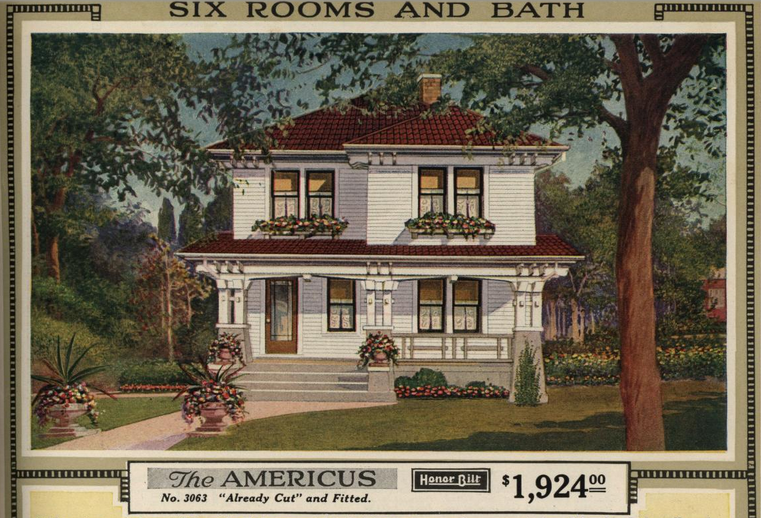

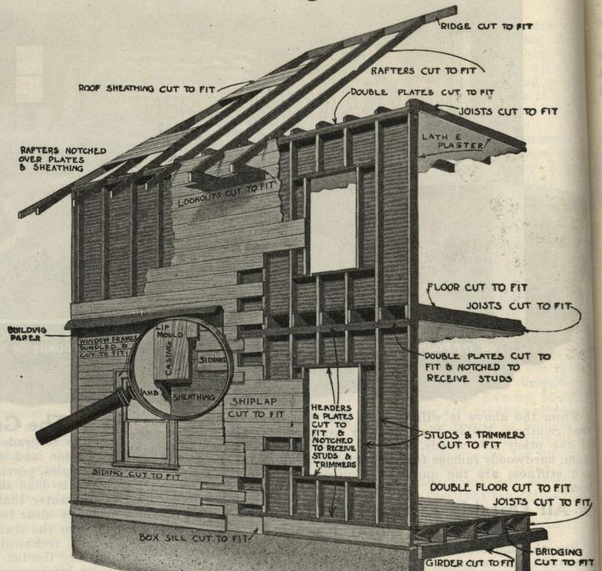

In the early part of the 20th century, an estimated 150,000 homes were sold in the US and Canada as mail-order homes – a kit you could buy from Sears or any number of other companies where pre-cut lumber, windows and other materials were delivered to your property for an assembly that would cost you a third of the cost of a regular new home. After World War II, the construction industry changed to favor tract building, where economies of scale were found in building hundreds or thousands of the same house on a large plot of development land – the typical North American suburb.

Then the mobile home, originally marketed to those who wanted to be able to move around, became a housing option that took advantage of economies of scale and a factory-built manufacturing process, becoming the new cheapest way to buy a home. Cheap housing, unfortunately, became synonymous with bad housing, offering poor comfort, little safety from mold, and materials destined for the landfill, not to mention the fact that manufactured (modular and mobile) homes became some of the most expensive homes to own because of their astronomical costs to heat and cool them.

Today – putting aside bad reputations and improving quality

As homeowners experienced some of the pitfalls of manufactured housing like quality control issues and substandard performance for comfort and energy use, the words “modular” and “manufactured” started to leave a bad taste in our mouths, and many likely swore to never consider such a path for their buildings. Call it a failure of building regulations or call it something else, the end result has been an increasing cost of construction to the point where instead of buying a house for $30,000 (roughly the inflation-adjusted value of a kit home from the 1920s), we’re spending an average of US$270,000 in the US and US$480,000 in Canada for a new home today.

The need to bring housing prices down is more crucial than ever. With better building regulations, a return to the efficiencies of the manufacturing process, and a values-based approach to construction, today we are starting to see high performance buildings with lower lifetime costs than those built on site to far lower standards of comfort, energy efficiency, and sustainability.

Unfortunately, where we’re seeing this succeed isn’t necessarily in North America. In fact, it is in places like Sweden, where 80% of new construction is built using prefabricated methods, that these costs advantages are truly making high performance construction competitive with substandard site-built construction.

Learning from our friends in Europe

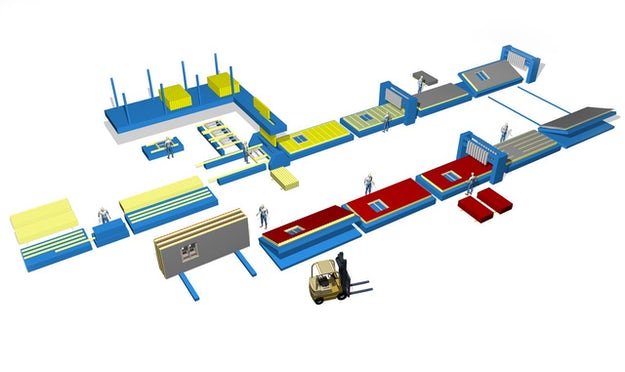

So how can we learn from what the Swedes and other European countries have done? It starts with recognizing the demand from consumers for better housing, and realizing that the only way to service that demand is to design and build these better-insulated, higher quality building envelope components in a factory. And because shipping large volumes of empty air isn’t necessarily economical, modules are for many reasons less favorable than what we call “closed” panels – structural panels with insulation, weather protection, and air and moisture control layers already installed.

Panels can be built under any kind of roof with any selection of tools, but the game-changing advances will likely only come from automated, computer-aided design and cutting tools that North America has been slow to adopt. But little by little, our industry is evolving, and quality and cost-competitiveness are becoming more and more synonymous with high performance prefab.

Getting it right

It is therefore not a new idea but rather the rapid adoption of an existing working model that presents an enormous opportunity for bringing construction of residential, commercial, and institutional buildings into the 21st century. But we won’t – and shouldn’t expect to – get there overnight. In fact, large prefab companies in the US area already closing their doors when trying to achieve scale too quickly, so the solution – we believe – will need to look more like what we see in Germany – decentralized, small prefab factories making reasonable use of automation technologies and scale to offer a competitive product that is local, efficient, and sustainable. Perhaps we just have to accept some failure from innovations and adaptations that aren’t in balance the ecosystem of housing needs – after all, isn’t that how evolution works?